Simms is one of the most remote ruins on the Anglezarke moors, lying south on the banks of the River Yarrow. The name is believed to be a shortened form of Simson, although George Birtill in his book Heather In My Hat suggested that “Simms = Son of Simon, possibly Simon De Knoll who was an early freeholder in Anglezarke.”

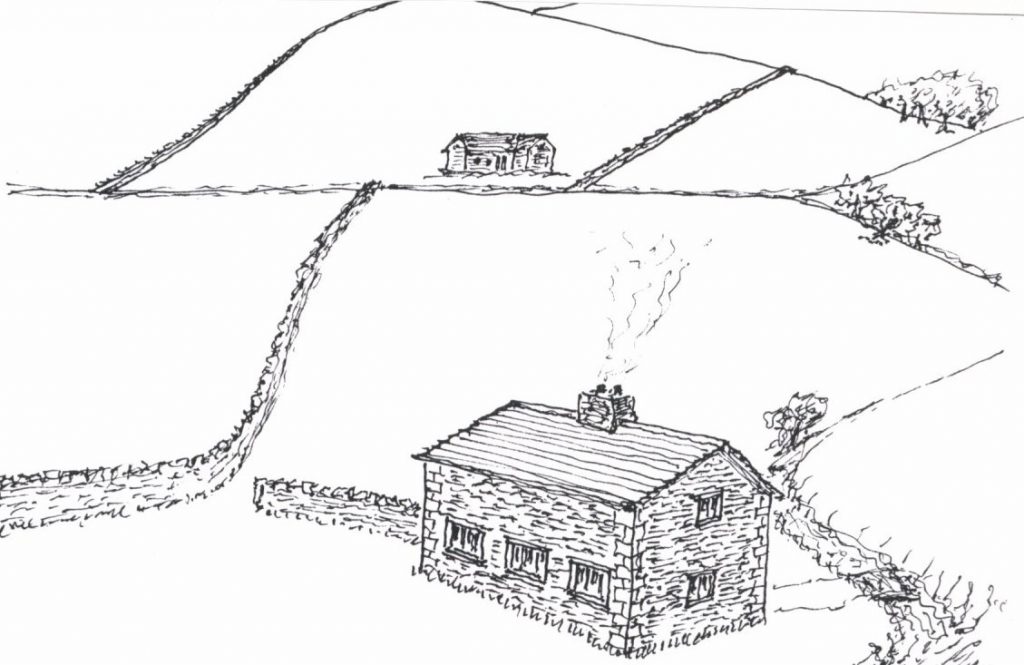

The area once had an abundance of farms, but even the ruins are disappearing as stone is taken for road building and other purposes. A friend recalled seeing Simms in the mid‑1990s “when there were still openings for windows and doors,” though today only fragments remain.

Families & Residents

The Pilkington family, who had links to most of the farms on the moors, are known to have lived here. Samuel Pilkington was born at Simms on 2 March 1809, christened on 13 June at Rivington Unitarian Church. He married on 18 January 1847, and died in 1887, buried at the Parish Church. His son Thomas lived from 1844 to 1897.

The 1841 census lists inhabitants of Simms — though this was actually Simms in Rivington, not Anglezarke:

- Thomas Latham, age 30, Farmer & Weaver

- Ellen Latham, age 30, Weaver

- Samuel Hampson, age 20, Labourer

- Alice Hampson, age 30, Weaver

- Nancy Finch, age 20, Weaver

Other tenants of Anglezarke recorded as far back as 1595 include Jepson, Ward, Gill, and Simm. A Roger Simm of Anglezarke is noted in 1731. By 1757, Simms had 108 acres — comparable to Higher Hempshaw’s (110 acres) and Lower Hempshaw’s (51 acres). Old Brooks, by contrast, had only 8 acres.

Farming & Daily Life

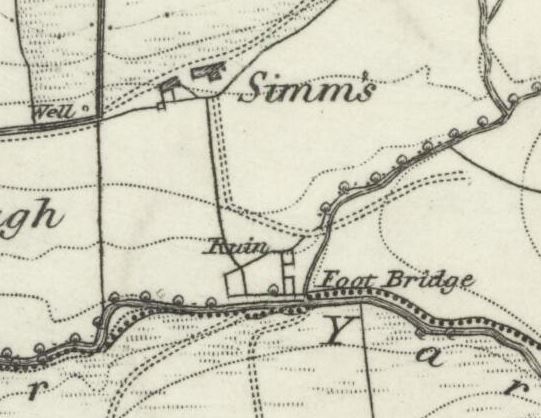

The farm was rebuilt in its “current” location in 1820 at the request of the tenant, moving northward from the original site known locally as Giant’s Stile Farm. The barn there was an old threshing barn, evidence of enclosure farming before extensive ploughing ceased around 1730–50.

There is a Simms in Rivington, a different property altogether.

By 1897, Simms joined with Hempshaw’s, with an overall farmed acreage of 267. The 1851 census confirms that Simms had a shepherd, as did Brook House and Higher Hempshaw’s. Ten years later, Simms along with Brook House, Lower Hempshaw’s, Parsons Bullough, and High Bullough all employed the farmer’s son as shepherd. Sheep were the mainstay, though “a few stirks (young calves) were generally kept.”

When occupied in 1897, the rent of Simms had dropped to 40% of the 1878 level, reflecting the agricultural decline of the moors.

Architecture & Features

Richard Skelton in Landings mentions “an unnamed and tattered book in Bolton Library that says there was a date stone on the farm of 1649.” The construction was said to include “an unusual form of roof truss, where the beam rests on the walls of the barn, and the roof is made of stone slabs.”

The area around Lead Mines Clough was known for open ditches across the moorland, rather than the more modern tile ditches that later replaced them.

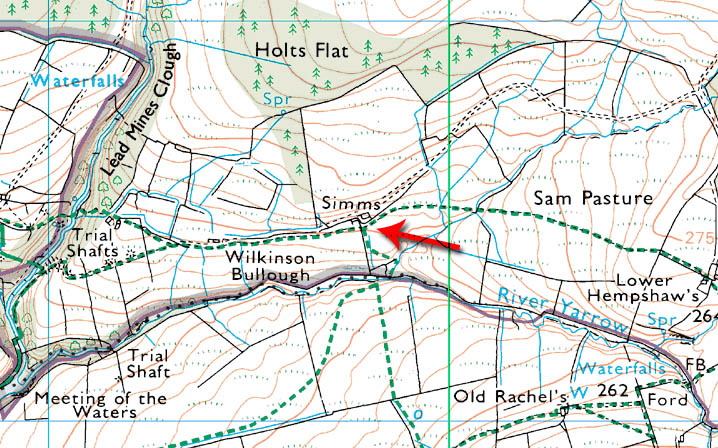

Maps show both the later location of Simms and the unmarked ruin near the river bank. “Perhaps the older ruin is in better condition due to it disappearing from mapping?”

Decline & Ruin

When Rivington Waterworks was constructed in the 1850s, landlords reduced the number of buildings in the water collecting grounds to prevent pollution of the supply. “Perhaps this is what happened here.”

By the late 1800s, farming was only a subsidiary income source, with men mainly working in the mills of Adlington and Belmont. The ruins of Simms were unmistakable for their size, but by the twentieth century they had largely collapsed.

Present Day

Simms remains one of the most remote ruins of Anglezarke. The outlines of both the later farm and the earlier Giant’s Stile Farm can still be traced.

The site is a prime spot for wheatear, curlew, and stonechat. Though ruinous, Simms endures in maps, oral memory, and archival fragments, its story tied to the Pilkingtons, shepherds, and the shifting landscape of the moors.