Hempshaw’s is said to be a corruption of Helmshaw’s. The valley here was described as the hamlet of Helmshawsyde in a document dated 1520, and Helmeshawes in 1566. The earliest mention of the spot is Elmshaw about 200 years before, which may describe the valley as “a small one where elm trees grow.”

The name itself has several possible derivations. Helm can mean “Top” or “Summit,” while Shaw refers to a thicket or copse. Yet the site is not truly a summit, so this explanation seems unlikely. Another theory is that Helm was a personal name, making Helmshawes a corruption of “Helm’s Haws (fields).”

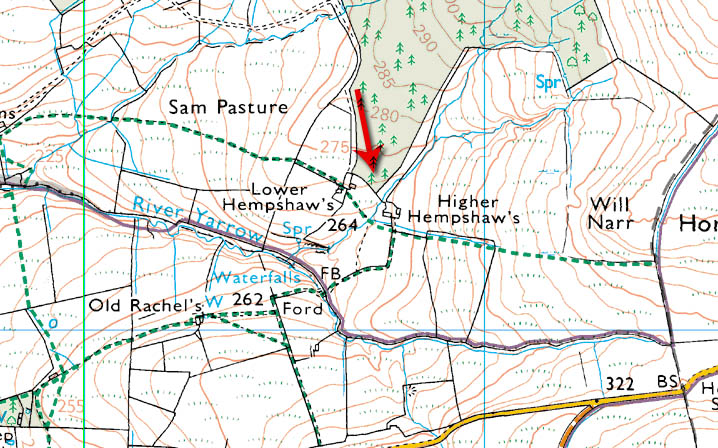

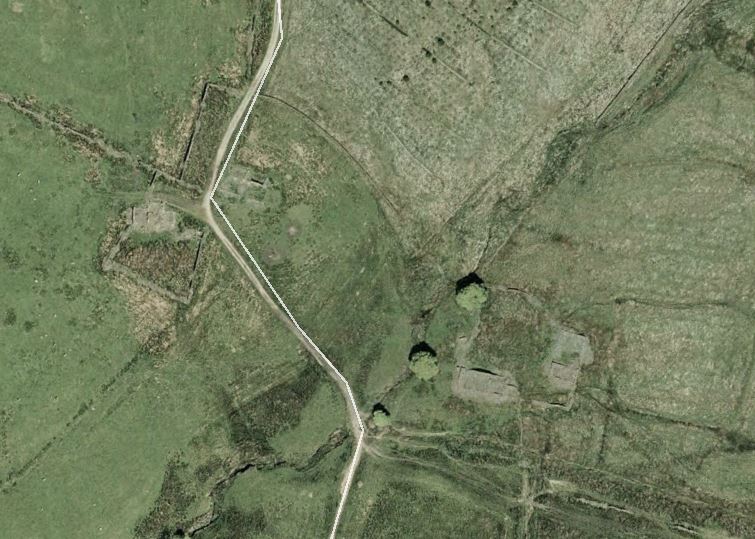

There are two ruins at Hempshaw’s — Higher and Lower. At least one of the ruins may have been two structures joined into one. The remains of a small close planted with trees suggest there was once a garden. The ruins of Higher and Lower Hempshaw’s are the only isolated farmsteads visible from the nearby roads.

Families & Residents

Both farms were inhabited by the Kershaw family in the 19th century. A stone in the left‑hand side of the farther gateway bore a rough inscription: “AF over 1741.”

The census of 1871 records a child, initials S.P., daughter of J.P. and E.B., born in 1865 in Anglezarke and living at Lower Hempshaw’s on 2 April 1871. On the next census she was listed as a farm servant, also in Anglezarke, quite probably still at Hempshaw’s. She later drowned in the Leeds–Liverpool Canal at the age of 21 or 22, and was buried in Rivington at the Presbyterian Chapel.

In John Rawlinson’s About Rivington (1969), the children of the last generation of farmers recalled their lives at Hempshaw’s. One told of leaving the farm to join the army in 1914, serving in Egypt, France, and Mesopotamia, and returning in 1919 to find his parents living in Horwich and the farm “empty and desolate.” Another story was of a young son being told by an aged farm labourer to “go quietly around these farms, because a lot of brave men are buried here.”

Farming & Daily Life

The farms were fed by Green Withins Brook, a tributary of the River Yarrow. The moorland hills flatten out here, making a typical place for an old farm. The name “Higher” was customarily given to a later house, not necessarily one higher on the hill.

The ruins today

A farmer and his sons made their own bowling green here in the 1890s, though “sadly, there is sign whatsoever of this now!” The lambing croft served both Higher and Lower Hempshaw’s, about five acres in size, surrounded by a now‑crumbling high dry stone wall.

Both farms had barns, brick floors in the cow stalls, and pig sties. Prosperity is indicated by plastered walls, a fireplace in the north end room, and a low stone bench. The south side of Lower Hempshaw’s had a lush garden with a flower bed edged in stone.

Architecture & Features

Higher Hempshaw’s had a fine barn, separate from the house, which was large and may have been two properties joined into one. The gateway stone inscribed “AF over 1741” remains a notable feature.

By 1936, Lower Hempshaw’s was already ruinous. The remnants of a staircase were still visible then, though not now. The ruins were described as “prosperous” in their day, with brick floors in the cow stalls and plastered walls.

Decline & Ruin

By the early 20th century, Hempshaw’s was in decline. The farms were abandoned, and by 1936 Lower Hempshaw’s was ruinous. The bowling green had vanished, and the staircase remnants disappeared soon after.

Rawlinson’s interviews in 1969 captured the memories of the last generation, who insisted the life was not lonely. They recalled shopping at the Co‑op in Belmont for sugar and supplies. When asked if their father let them have a horse, one replied: “Oh no. He said it were too rough for a horse, you must take your sister.”

Present Day

Today, Hempshaw’s survives only as ruins, visible from the nearby roads. The outlines of Higher and Lower farms remain, with gardens and walls still traceable. Drone footage shows the two sites clearly, reminders of the families who lived, farmed, and endured here. Though abandoned, Hempshaw’s remains one of the most evocative ruins of Anglezarke, its stories preserved in census records, gravestones, and oral history.